Over the weekend, I had the opportunity to speak at the Children's Books Ireland International Conference. During my presentation, I shared details about my background, upbringing, and love for books, languages, and Ireland. If you cannot attend in person or tune in to the live stream, the conference organisers will be uploading recorded video sessions to YouTube for a limited time, but if reading is what you love, keep going.

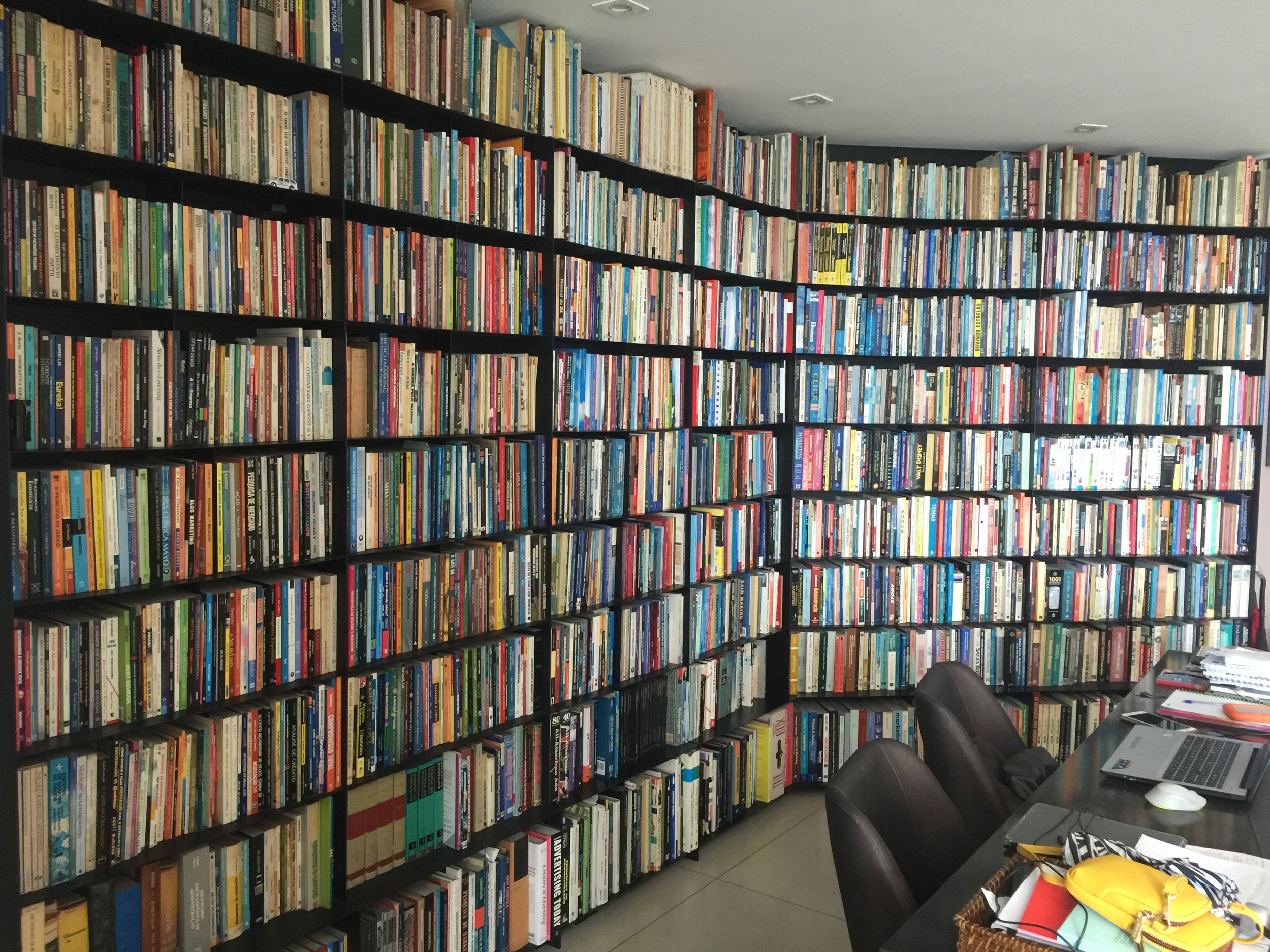

When I was little, I loved books. Not because I was particularly attracted to them but because they were all around me. You see, my grandparents from my father's side were illiterate, and when he learned how to read and that you could learn from books, he became obsessed.

Therefore, I grew up with books covering almost every surface of the apartment where we lived. Being an only child has its perks. He left strategic books within my reach: the classics, thesaurus, and a myriad of dictionaries. And when I had a question, there was no Google, then he'd pick a book from the shelf, and we would find out the answer together. Books were so ever-present that when my dad and I would go for walks, he'd bring a book, and I would bring a comic book, and like much like a comic strip, we'd walk around the neighbourhood, noses stuck in our reads.

So, from a very young age, I learned how to love learning and figuring things out, and I feel very lucky that curiosity was always celebrated in my upbringing.

When I was around eight years old, it was the first time I heard people speaking to each other in English. And I remember clear as day, my teacher speaking to another teacher, probably something I should not know about, and my jaw dropped: Do you... Do you understand what she's saying? They nodded their heads.

I knew it then: My teachers were, in fact, spies! Sharing ideas and things in a way that I could not understand, but they could. And I wanted in!

What seemed like gibberish to me had meaning to other people!

So I set off to learn English, and as a teenager in the late 1990s, I had three excellent reasons for it. I loved the band Hanson and listened to their songs over and over again, not only their music but many other artists, too. The Beatles were also a favourite but for different reasons. Slowly, I saw the world opening up new possibilities to me. I was lucky enough to spend six months, on my own, studying through the last months of high school in New Hampshire in the United States, where I sharpened my English skills and, upon returning to Brazil, obtained a degree in Letters - English and Portuguese, and became a teacher. At the same time, I also obtained a degree in Digital Communication, which gave me, in counterbalance, other pragmatic skills, like learning some software and marketing. All the while, I had learned Spanish, and I began studying German. Like my father's obsession with books, I fell in love with languages. In my early twenties, I was sure that I would become a university professor. And that's when Ireland happened.

Ireland wasn't much on my radar when my then-boyfriend, now husband, and I decided we wanted to spend some time abroad. We did some research and decided that we wished to go to an English-speaking country for a better chance to find work and have a better experience. Luckily, one of my professors at university knew a Peter O'Neill, Irish turned Brazilian resident who could give us some scoop on the country. He told us about the Luas and Ryanair and the North and South sides of the Liffey. Ireland was having a moment (Celtic Tiger anyone?), but, above all, people were lovely. And we were off to the libraries; I read the Inis website back to front on immigration and visas, and we rented DVDs to discover what the country was about. So, from our research, we gathered that 1) Ireland had unpredictable weather, 2) some exciting job opportunities and 3) incredibly welcoming people.

So we arrived in Ireland, and two weeks in, I got my first job on the island designing Irish souvenirs. I had a blog with some of my drawings and used it as a portfolio to apply. It was a risk, not having an art degree, but I knew that speaking English would be fine for the interview, but I needed to figure out my work. And getting that job was enlightening because that's when I discovered I could make money drawing. I've loved drawing since I was a child, and I got told off all through primary school to the university about it, but I never thought I had the skills to work with it. Also, being on Ireland's tourism and commercial side was very helpful in understanding how Irish culture was portrayed and what it meant to different people. Irish prayers and sayings, what the landscape was, what people were proud of, what they were embarrassed about, what they wanted to share.

What's the story?

But there were challenges regarding the language; I was sure this was an English-speaking country, but gosh, it was challenging to understand what people were saying. Firstly, if you studied English grammar, you'll have a hard time figuring out when people say things like "Did you hear from yer man?" or "I'm after coming from the shops with the messages. Do you know why? Because that's Hiberno English, a set of dialects native to Ireland that, if you are not from here, can cause quite a bit of noise communication.

I was having enough of a hard time figuring out that deer means expensive and that "when you have a minute" actually means “right now”. Let alone give the Irish a chance. And that's one of the funniest things about language. We are all polyglots in our own language. Not because some people speak Hiberno English, I'm sure some people don't, but because we shift the way we communicate depending on who we talk to. We use different vocabulary and structures when addressing different people, like the Uachtarán na hÉireann or the local barista. The same happens when we confide in our best friend or write a bursary application. Language is fluid.

And because figuring out Irish on my own was proving itself to be impossible (I was trying to run parallels of the Irish and English versions I could read), I began enquiring: Are there people who speak Irish? Because I see it everywhere: street signs, license plates, official documents, roads, the name of the police...

Here's what I heard:

"No one speaks it."

"It's a dead language."

"Irish has no use."

Being a foreigner who didn't know any better, I took people's word for the truth. And I left Irish alone. Soon enough, it became noise, like music in an elevator.

Then, a major economic crisis hit the world, and I was looking for other work opportunities. I was freelancing with translation, teaching and some drawing work while taking a couple of art classes, one of them in writing and illustrating children's books. Those gave me some incredible friendships and connected me with other children's bookmakers and the certainty that I wanted to work with books for children. With my newfound partial confidence in my art being good enough to do commercial work, I then applied for Illustrators Ireland to gain more credibility and be part of a supportive community, but I did not get in. While I waited six months to apply it again, I began crafting a consistent portfolio and looking for clients to make that happen. I made some postcards and sent them to every Irish publisher I could find that made children's books. In Irish fashion, many replied with extreme politeness, saying they weren't looking for illustrators or that it wasn't a fit. However, I got one response from a small publisher in Spiddal that only published books in the Irish language, and his response was very different. Tadhg, from Futa Fata, told me that to be in children's publishing, I had to showcase something different, not the postcards I sent, but something that related much more to children, perhaps my version of a known fairytale. As a matter of fact, he gave me pointers on other things I could include in my portfolio, and I was ready to go with it all, but there was a big bump on my way.

Six months into motherhood, I heard from Tadhg again. "I have a story from Máire Zepf, and this is her début picture book, and I think you'll be a lovely fit for it." And in the blur of that first year, after my husband got home from work from 8 pm to 3 in the morning, I illustrated Ná Gabh Ar Scoil!

But how did I illustrate a manuscript written in Irish if I didn’t speak it?

Well, Tadhg was kind enough to provide me with English translations of the work. Although I lacked the nuances and some sensibility from the original language, I did my very best to communicate the emotions and feelings I got from the English manuscript into the images I made. After that, Tadhg asked me to illustrate another book, one inspired by music and this time with four other illustrators. So, on top of the translations, I asked to listen to the songs so words, melodies and rhythms could help inform my work. I still could not speak or understand Irish, but I wanted to write books, too. I wanted to know if I could maybe write things in English and have them translated into Irish, and at that moment, I discovered something: There is a market for translated works from English into Irish, but a lot of the connection in the Irish-speaking community, especially through children's books, is through events in Irish. And there aren't many authors who can do those events and even fewer illustrators. Hmmm. Challenge accepted!

With the experience of creating more and more books with Futa Fata and then facilitating numerous bilingual workshops, mostly with author Sadhbh Devlin, I noticed that there were a LOT and, I mean, a lot of people who actually spoke Irish every single day. Some were self-conscious, but some were hardcore speakers. This is when I discovered what I call "The Secret Society of The Gaeilgoirí". Sadhbh, for example, has only worked in Irish throughout her career, and all the opportunities in her working life have come from being able to communicate in Irish. Former Laureate na nÓg Áine Ní Ghlinn talked a lot about the Cloak of Invisibility around the Irish language, and this is how things felt to me. Now the curtain was down, and just like when I was little and realized that my teachers were spies (I mean, who is to say they weren't?!) I knew I wanted in, too, especially because this had even more meaning.

Language is a living expression of culture but can also be used as a tool for oppression. When a language is superimposed over others, as in many colonized countries, the attempt is not only to make people speak like the coloniser but also to erase the culture, stories and heritage of those colonised. I know that because I speak Portuguese, not Tupi or any other native indigenous Brazilian language. But what I know from speaking other languages, including illustration, is that a language can expand our horizons, change our points of view, and create new perspectives to understand the world and new possibilities. And isn't that what children's books do too? They make us more empathetic and open; they show us things we didn't see or know before. Languages and children's books go hand in hand, and they say: "Let me show you the world through my eyes".

Because I have no bias or trauma regarding the Irish language, I see it as a gift. A gift to see and understand the world in a way that, not too long ago, I only had but a glimpse of. So, my husband and I decided to enrol our son in a Gaelscoil because we want him to have that gift that we don't have but can provide him with. I began studying Irish with him through his obair bhaile; I took courses at Conradh na Gaeilge and Gaelchultúr and took up daily practice through Duolingo. But what truly made the difference in learning Irish for me was having support. People who were always delighted with my Gaeilge Bhriste, who still have the patience to hear me using an Teanga, that reply to my emails and texts in Irish. There has always been joy in exchanges using Irish. I also began studying with my Brazilian and language-nerd friend Bárbara, who, during the pandemic, took up on Irish and asked if I wanted to join her. We bought a couple of self-study books and an Irish grammar, and since then, we have been diligently studying Irish every week. And this past July, we went to the Gaeltacht in Spiddal for a week to learn and speak Irish, staying with a Bean an Tí and even having dreams as Gaeilge.

From day one, my experience in Ireland has been mutual love. Ireland opened its arms to me, and I embraced it back. I hope that children (and children at heart) can see themselves through my work. Be it through the English language books that I make that are inclusive and diverse, which I believe reflect what Ireland has been becoming, or through the books in Irish that reach into the Irish-speaking communities and beyond, to children like my son, who didn't have a word of Irish at home, but the heart to embrace it.

I know I discussed a lot about languages and connections and didn't quite mention risks and rewards because, personally, I think the word "risk" evokes a notion of fear, and I prefer to see 'risks' as opportunities. It's a matter of perspective. All these things: Choosing to read certain books, learning certain languages, moving countries, choosing a university course, making souvenirs, and even illustrating books in a language I didn't speak can all be considered risks or opportunities. Failing or not at those is also a matter of perspective because when you take a risk or opportunity and don't succeed, it's because the outcome is different than your expectation. So you can either celebrate things going your way or learn from them taking a different direction.

You have a GIFT

You have the gift of seeing the world through a language that a lot of people in the world don't. You have the gift to keep the Irish heritage and culture alive. It is what makes you unique and authentic. You have the power to transform and create new relationships with the language. Ireland is a very new yet ancient country, and we are part of Irish history. It is up to us to choose the legacy we will leave for the children of the future.

I want to finish this session with a little excerpt from a song I used to sing with my dad as we walked around the busy streets of São Paulo (once we were not reading, of course). It's called "Como Uma Onda No Mar" by Lulu Santos. It has a tropical feel-good vibe, with seagulls and waves swishing in the background, and the lyrics start like this:

Nada do que foi será

De novo do jeito que já foi um dia

Tudo passa, tudo sempre passará

A vida vem em ondas

Como um mar

Num indo e vindo infinito...

Nothing that is will ever be

Again, the way it once was

Everything goes, everything will go

Life comes in waves

Like a sea

an infinite going and coming...

Take that risk (or opportunity). Share your stories and dreams.

Write your book. Speak your language.